Keep yourself updated with the latest developments at Astrum. Get the latest press releases and read what’s kept us in the news.

The growing digital economy of the Indian election machine

Gurgaon, Political parties’ digital campaigns are getting increasingly sophisticated in technology and strategy, and a wave of companies new and old are cashing in The 2019 Indian elections, which begin in less than a week, loom large in Diggaj Mogra’s life. It’s all he has time for. “If you were to register as a candidate today, by tomorrow you would have 50 different companies calling you saying, ‘We’ll do SMS for you, give you databases, etc.’,” says Mogra, a director at Jarvis Consulting. A Mumbai-based election strategy and tech company, Jarvis (like the AI in the Iron Man films) was founded by two former executives at cab aggregator Ola Piyush Jalan and Piyush Gupta—in December 2016.

“Digital”, “technology” and “social” have dominated the Indian electoral lexicon ever since the 2014 race dubbed India’s first “social media election”—courtesy the campaign of the now-ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP. In the five years since, having a social media or digital presence has gone from being cutting edge to the baseline for India’s political parties. But for Mogra in his late 20s now; a computer engineer by training and an election strategy specialist for the past five years or so that’s all blase. “We don’t do things like social media campaigning now,” he says when we meet for a quick cup of tea at a cafe near his New Delhi office.

Jarvis focuses on data analytics voter trends, micro targeting, the whole package—as well as developing tech to help parties coordinate internally. Think tracking and monitoring the supply of resources and funds across states, districts and blocks.

The company, adds Mogra, is working on analytics for this year’s election for its clients. He declined to identify them (or reveal much in the way of details about his work) but did mention that they work with both individual leaders and political parties as a whole.

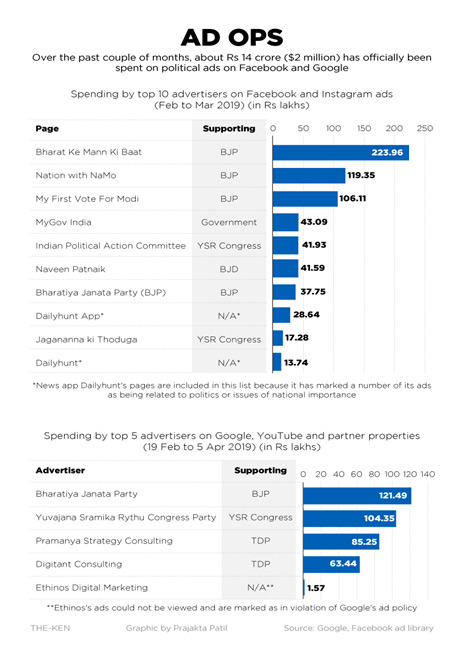

Indian politicians are expected to spend anywhere from Rs 600 crore ($86.7 million) to Rs 5,000 crore ($722.9 million) to Rs 12,000 crore ($1.73 billion) on digital campaigns in the upcoming national elections. Depending on whom you ask. Election spending is a notoriously difficult metric to measure in India, given the vast amounts of off-the-books expenditure.

But everyone is in agreement that digital expenditure has been rising, even as a proportion of total spending. “Political parties’ digital media spending is up from 5% [in 2014] to 25% now,” says Vineet Sodhani, CEO of marketing and media advisory firm Spatial Access. And everyone wants a piece of the pie.

In an interplay of democracy and capitalism in the world’s biggest (and perhaps most expensive) elections, analytics and digital marketing companies are seeing a burgeoning political market. Following the lead of the BJP, political parties of all hues are building formidable in-house tech teams and increasingly turning to professional firms. Traditional media agencies, digital marketing and adtech startups, polling and data analytics specialists. All are either in talks with political parties or already working with them. This, apart from a veritable cottage industry of IT vendors offering cut-price “bulk SMS services” and “election management software” to the not-so-discerning candidate.

With social media as the bare minimum, serious money is now going towards digitising entire campaigns. And it could permanently alter the way elections in India are run.

Slice and dice

“My work starts two years ahead of an election and ends about three to four months before,” says Ashwani Singla. He is the founder and managing partner of reputation management firm Astrum, which advises corporations, governments and politicians.

From 2014 to today, the major political parties have grown increasingly sophisticated in their attitudes towards data, Singla says over the phone. “We mine and crunch publicly available datasets combined with extensive polling. All legally available, legitimate data,” he adds in a measured baritone.

For political campaigns, Gurugram-based Astrum offers election campaign strategy for voter segmentation (identifying “advocates”, “adversaries” and “winnable/swing” voters), battleground selection and an assessment of “candidate attractiveness and positioning”. Their pitch in a line: “There is no second prize for losing an election. We help you win.”

Singla with about twenty years of experience in the PR and market research industries also acted as a campaign strategist for the BJP during the 2014 general elections. A year later, he launched Astrum, focusing on “science based, specialist reputation advisory services,” according to an article in the Holmes Report.

A little bit of contemporary history here. The genesis of the digital media and tech wave in Indian politics, by most accounts, can be largely traced back to two groups. The first is the BJP (which, notably, is the country’s richest party, according to publicly available figures at least). In the early 2010s, the party built up its tech team, or “IT cell” in Indian political parlance, from setting up online campaign donations to getting leaders on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

The second was a group of “volunteers”—analysts, engineers, data scientists and more led by the political strategist Prashant Kishor, initially called Citizens for Accountable Governance, or CAG. Kishor and CAG later the Indian Political Action Committee, or I-PAC are often credited with delivering the BJP’s landslide win in 2014 (as well as a number of other elections for various parties).

Kishor eventually entered politics, joining the Janata Dal (United), an ally of the BJP. I-PAC, meanwhile, still operates as a consultancy of sorts for political parties, but more importantly, most political consultants, analysts and media executives The Ken spoke with all identified

Kishor and his group as the first set of “professionals” in the election campaign business. Which sets the stage for where we are today. “Many people I worked with have scattered from CAG and I-PAC and been hired by politicians and parties across the country,” says a former I-PAC member, who asked not to be named. “Today, the top one-third of leaders in any important party has a team of advisors [on tech and digital platforms],” separate from whatever agencies the party, as a whole, signs on. Each looking for an edge over rivals both within and without.

And in this ecosystem, the consensus view is that the BJP is, without a doubt, several years ahead of the pack.

Keeping it in-house

“The first time I remember the use of technology in electoral politics was during the 2004 general elections, when we all started receiving IVR calls in the voice of Mr Vajpayee, and we have come a long way now,” says Ankit Lal, a social media and IT strategist with the Aam Aadmi Party, or AAP. The reference is to automated phone calls by the BJP—led by then-Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee as part of its 2004 campaign (which, incidentally, it lost).

The BJP, Lal agrees, has consistently been in the lead when it comes to both social media and technology in general. The AAP in power in the national capital territory of Delhi, and with four seats in the 545 member lower house of Parliament though, prides itself on its volunteer-run election operations and its own in-house tech team.

And to be fair to Lal, some political rivals and marketing executives The Ken spoke to agreed that the six year old party is fairly tech-savvy. “We’re working on a CRM (customer relationship management platform) of sorts now,” adds Lal, who points out that his party (heavily reliant on individual donations) is an outlier because it doesn’t sign on any external firms for its campaigns. The “CRM”, in alpha testing, is something the AAP is banking on to connect its network of volunteers—especially in disseminating content and messaging.

Then there’s the Congress, the largest opposition party in Parliament. Like the AAP, the Congress has been beefing up its internal tech operations in preparation for the elections. It’s even launched a dedicated app last month to coordinate millions of party workers. Over the past two years or so, the Congress has really revamped its social media game. It’s a trend that’s visible across parties, with regional parties such as the Biju Janata Dal in Odisha and the YSR Congress in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana among the top spenders on political ads on Facebook.

“The BJP has a five-year headstart,” admits a person who’s worked on the Congress campaign, speaking on condition of anonymity. But, this person adds, the party hasn’t been sitting still it’s working on improving its targeting across digital platforms, as well as campaign-monitoring tools. And, of course, spending on social media teams and advertising. And unlike the AAP, the incumbent BJP and the Congress have had no hesitation about hiring external talent or third-party firms. Traditionally, this sort of role was the domain of conventional media buying and advertising agencies like Madison, Ogilvy & Mather (O&M), Dentsu and GroupM. All of which are still well in the game. Madison, O&M and McCann, for instance, worked on the BJP’s winning 2014 campaign, and the first two have been signed on for this year’s electoral battle as well. But as the market broadens, parties and candidates are more open to newer companies and startups. And for some, there’s not much of a choice.

Bottom of the pyramid?

The Congress, for one, has signed on a set of niche creative and advertising companies to handle its 2019 digital campaign. One of those companies is DesignBoxed, a digital marketing firm headquartered in Surat, Gujarat. It also has an office in Chandigarh. DesignBoxed was founded in 2011 by Naresh Arora, a textile-designer-turned-marketer from Punjab. “There’s a dearth of a professional approach in this field, with very few major players,” says Arora, who spotted an opportunity after the 2014 elections—in 2015, DesignBoxed changed to a “full-time” political campaigning company. Today, it has over 200 staff and has worked with the Congress on state elections in Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh as of December last year. This time around, says Arora, DesignBoxed has already launched campaigns like ‘Shut the Fake Up’, which targets fake news. What stands out about DesignBoxed is not its technology or technique, but that it represents, in a way, a new breed of political marketer. Unlike specialised analytics and tech firms or major advertising and media agencies, Designboxed has significant reach among politicians in small-town India. “We have a variety of clients (individual candidates and also parties), with many from tier-2 towns and even rural areas,” says Arora, who counts his family’s political connections as an inspiration for his agency’s pivot. But go further down the ladder of specialisation and technological sophistication and you’ll find a horde of small IT businesses at its base. All of these have pivoted to offering the sort of basic social media and communications services that became the bare necessity for political candidates in the wake of 2014.

“Management + Data + IT = Big Success In Election”

JANADHAR ELECTION SOFTWARE

Take Delhi-based BOL7, which offers everything from filming commercials to trademark registration to… real estate consultancy on its website. And, of course, “election management”.

“Locally, you’ll find a lot of these vendors who provide everything from SMS marketing to database management,” says Savio Joseph, co-founder of digital marketing agency Teen Bandar (which at one point also specialized in political campaigning). A cursory Google search throws up the likes of Creativizt (Delhi), Janadhar (Jaipur) and Nimbus IT (Noida), who list access to mobile number databases, bulk SMS and WhatsApp messaging, and Twitter feed handling as services on offer. A slightly more advanced version, Joseph says over the phone, might be something like NationBuilder, a US-based software company that gives American politicians access to reams of voter data. (And also miscellaneous services like setting up your own website). But while all these firms, as well as the more technologically-advanced ones like Astrum and Jarvis, offer a seemingly bottomless list of services, results, for now, are often a mixed bag.

‘Early days’

“We’ve run several campaigns, which have all been successful so far,” says Astrum’s Singla. “But there’s no replacing feet on the ground for voter activation. If you don’t have that, it doesn’t matter what data you use.”

Mogra of Jarvis echoes the sentiment: “We’re doing a lot of very interesting work this time. I can’t tell you about it just yet, but we’ll have a lot more information after the election.” But in terms of actual impact on the ground? “It’s still somewhat limited,” he says quite candidly—

but he’s not fazed. It’s a long-term project, with the biggest hurdle being the lack of good data.

Data vendors, from telecom retailers who sell lists of phone numbers to contractors who have worked on government projects (and so have access to government databases), are notoriously unreliable in India. And opinions are divided on publicly available information.

“India, ultimately, is still at a state where many parts of the country are effectively media dark,” says Deepa Bhatia, general manager of UK-based YouGov in India. The market research firm—which specialises in political surveys and polling has worked on a number of campaigns for parties in the UK, and is in talks with major parties in India as well, says Bhatia, declining to name these potential clients.

“However, what we see in more developed markets is that our conversations start two or even three years before an election. In India, they’re still looking for solutions right before the elections,” she adds. And even though the country is estimated to have some 450 million smartphone owners, that would, at best, be about half the 900 million voter base, somewhat limiting the scope of online polling methods such as those favoured by YouGov.

For context, political parties’ current digital avenues of choice are increasingly coming under pressure.

Facebook, for one, announced just this week that it had shut down hundreds of pages linked to the Congress and a BJP-affiliated tech company for “coordinated inauthentic behaviour” using fake accounts. Those pages reached millions of followers. WhatsApp, perhaps the most popular battleground for political messaging in the country, has over the past few months announced a slew of measures aimed at curbing fake news, propaganda and spam. It capped the number of times a message can be forwarded, added new privacy settings for group messaging (thousands of groups are used to target voters) and has cracked down on spam accounts.

“WhatsApp won’t work as well anymore. In the Rajasthan elections [in December 2018], WhatsApp shut down some 95,000 accounts,” says Mogra. While the messaging company does not put out these numbers for India, a February report from WhatsApp mentions that its systems ban 2 million accounts a month globally for “bulk or automated behaviour”.

“There are brands that are spending Rs 200-300 crore ($28.9 million-$43.4 million) on digital every year, and even they haven’t figured out just the right way to handle digital marketing,” says Sodhani of Spatial Access. “With the political parties, when it comes to actual plans for digital/tech campaigns, it’s quite haphazard and nebulous. Not so much because they don’t want to share, but because there’s this lack of clarity, with different people saying different things.” “It’s still early days,” says the person cited earlier who worked with the Congress campaign. “And there are ways of getting around [poor quality data] though, of working with the data. We’re doing that—you may not see the impact right now, but it will work out over the next two or three cycles. It’s only going to get bigger.”